The America’s Cup is the oldest sport trophy, but over the 168 years it has been in play, history shows that events have invariably been far from sporting. Even today, stakeholders in the cup are playing just as fast and free with the rules as they did in the 19th century, especially when they are the holders. But not only them. This is part 1 of the big GOOSE America’s Cup history in three parts.

Part 1: The early years

Members of the New York Yacht Club (NYYC), which famously retained the ≫Auld Mug≪ for 132 years – a record run for any sporting trophy –, did so by turning Machiavellian deceit into an art form. They were finally beaten at their own game in 1983 by the swashbuckling Australian fraudster Alan Bond whose team and yacht, the famous wing-keeled wonder Australia II, ran rings around the club’s autocratic boater, bow tie and striped blazer wearing Cup committee onshore, and all competition including Dennis Conner’s defending yacht Liberty II on the water. The 1800s was a period in American history when huge fortunes were made in a relatively short time, and much of that wealth was centred in New York. Membership of the NYYC was a reflection of East Coast society at the time – ambitious, brash, confident and motivated. The big players included the likes of the Vanderbilts, whose family fortune had been built on the railroads, the Rockefellers (oil), Carnegies (steel), Bennetts (New York Herald) and the Morgans (banking), all hard-living rich amateur sporting types who filled their days with horse and sailboat racing, often betting huge sums on a single outcome.

The original challenge was just that – an opportunity to bet on American design prowess against the best British yachts racing under the White Ensign of the Royal Yacht Squadron (RYS) at Cowes. Though well able to pay, the five syndicate owners of the newly built schooner America hedged their bets by telling the builder that they would only pay if the yacht proved to be a winner! John Cox Stephens, the first commodore of the NYYC, and George L. Schuyler, two of the five, initially played down their hand answering a letter of hospitality from the RYS, writing of the ≫sound thrashing we are likely to get by venturing our longshore craft on your rough water.≪ Unfortunately, they foolishly showed their hand during an impromptu skirmish against Lavrock, the pride of the British fleet, at the end of their transatlantic delivery trip. Despite her heavy load – extra sails and as Stevens himself wrote ≫sufficient provisions to sail, if necessary, a long trip to India≪ – and starting 200 metres behind and to leeward, America soon climbed up and ahead of a stunned Lavrock crew, and pulled out a third of a mile lead by the time the RYS castle battlements were abeam.

Word shot round faster than startled pheasants. America was fast…very fast! As a result, no British owner would race or bet against the American invader whose owners were offering to accept any wager between 1,000 and 10,000 guineas. The stand-off became embarrassing … so much so that ≫The Times≪ newspaper commented: ≫America has the appearance of a sparrow-hawk among a flock of wood pigeon…The effect produced by her apparition off West Cowes among the yachtsmen seems to have been completely paralysing.≪ This public pressure forced the RYS to invite America to compete in the final event of the Club’s 1851 five-day regatta – a 53 mile race around the Isle of Wight and a new trophy, the RYS £100 Cup. The £100 refers to the cash prize on offer, not the value of the Cup, which is a rather gaudy production trophy bought off the shelf from the London jeweller Garrard. Over time, it has become the Holy Grail of yachting, but as a cup it is a useless artefact. The design is so top-heavy that it would fall over were there not a bolt running through it to hold it in place, so any celebratory champagne poured into the bowl simply runs out at the bottom.

The RYS membership may not have laid much importance to the event, but as a public spectacle, this ≫America versus the rest≪ had great significance; the ≫Times≪ correspondent painted the picture: ≫In the memory of man, Cowes never presented such an appearance as upon last Friday. There must have been upwards of 100 yachts lying at anchor in the roads, the beach was crowded from Egypt Point to the piers, the esplanade in front of the Club thronged with gentlemen and ladies, and the people inland who came over in shoals with wives, sons and daughters for the day. Booths were erected all along the quay, and the roadstead was alive with boats, while from the sea and shore rose an incessant buzz of voices, mingled with the splashing of oars, the flapping of sails, and the hissing of steam from the excursion vessels preparing to accompany the race.≪

Of the 18 starters, America was one of the last to raise anchor, but was soon cutting a wake through the fleet. She was 5th around the first mark, No Man’s Land buoy in the eastern Solent, and moved into the lead on the reach towards the Nab Lightship. It was here that the first of many Cup controversies unfolded. It was usual practice when racing clockwise around the Isle of Wight to round the Nab Lightship, but the sailing instructions given to America did not specify this and her skipper Dick Brown decided to cut the corner and head straight for St Catherine’s Point, saving several miles, while everyone else followed the traditional course. America went on to win, but after the finish, George Holland Ackers, owner of the 392 ft 3-masted schooner Brilliant, issued a protest. It was to no avail. Capt. Brown simply produced the sailing instructions he had been given which proved different to those handed to the rest of the fleet.

With Queen Victoria taking a keen interest in the race, the RYS had no wish to turn this into an international incident and the protest was quietly withdrawn. As Daniel Charles noted in his historic documentary on the Cup: ≫A gentleman’s yacht has won a gentleman’s race, despite its not very noble behaviour.≪ So, in a way, the America’s Cup was born from a bureaucratic cock-up, the first of many that now litter the event’s 168-year history. America’s owners quickly tired of the yacht, selling her soon after for £5,000, and within a few years they became equally bored of passing the Cup between themselves (or cleaning it) and planned to melt it down to produce five commemorative medals. Only one, George Schuyler dissented. He wanted to present the trophy to the NYYC to encourage international competition and was charged with drawing up the terms of reference. Known as the Deed of Gift, his third re-write, dated 1887 and lodged with the New York Supreme Court, essentially sets out the rules of the game that still apply today.

The document speaks about ≫friendly competition between foreign countries represented by an organised yacht club having for its annual regatta an ocean-water course, or an arm of the sea.≪ But as these events have unfolded, they have rarely been ≫friendly ≪, more ≫win-at-all-cost≪, and millions have been spent on lawyer fees in attempts to exploit loopholes in the historic wording. The most blatant has to be the challenge and later successful defence of the Cup by Swiss club Societe Nautique de Geneve. Americans are notoriously bad at geography, but surely New Yorkers know that Switzerland is a land-locked country! From the outset, the cards were stacked against the challengers. First, the challenging yacht had to be strong enough to sail across an ocean to attend the event, then face multiple competition against much lighter home-grown American vessels designed simply to excel in the inshore waters of New York Habour. Challenging yachts had not only to be designed and built in the country of challenge, but all equipment including sailcloth had to have emanated from there too. The same applied to the crew. The NYYC made no such restrictions on the defending yachts.

The first four challenges were lodged by British owners – the cantankerous James Ashbury, a self-made millionaire full of selfimportance (1870 and 1871) and the equally obdurate Earl of Dunraven (1893 and 1895) whose old money values and colonial attitude brought out the worst in the pretentious NYYC. Ashbury’s dealings with the American club were fractious from the start. He wanted a one-on-one match on open waters with his yacht Cambria against NYYC’s champion yacht. He got neither. Instead, Ashbury was invited to race in the Club’s annual regatta inside New York Harbour against 17 American yachts. Cambria finished 10th on handicap, having been forced about half a dozen times while on starboard (right of way) tack by boats on port tack steered by skippers who had little knowledge of the racing rules. Ashbury did what many subsequent challengers have done – he called in his lawyers!

Arguing that a ≫match≪ by definition should be a race between two yachts on equal terms, he won support from an unlikely quarter – George Schuyler, author of the Deed of Gift. He wrote to the Club saying that to force a lone challenging yacht to race against a large fleet of defending yachts was a clear departure from both the letter and spirit of the rules. Ashbury saw this as a victory of sorts and challenged the NYYC to a second one-on-one match the following year. He telegraphed the Club saying that he would arrive that autumn representing twelve clubs and proposed to sail one race under the colours of each. The New Yorkers agreed to a multi-race series and Ashbury’s demands for a fairer course offshore, but rejected the multiple club proposal, saying that he could only race under one flag – that of the Royal Harwich YC. But there was also a sting in the tail. While conceding to most of Ashbury’s demands, the NYYC set one of their own: the American club would be represented by four yachts and only on the morning of a given race would it decide which to use on that day. The game was lost before it had even begun. Ashbury’s Livonia lost the protest-ridden seven-race series 4:1 and returned home a bitter and disillusioned man.

Next to the slaughter was James Bell’s Scottish challenger Thistle. This George L. Watson design was built in great secrecy with her hull and keel hidden from prying eyes by a canvas shroud similar to the one that shielded Australia II’s controversial wing keel 96 years later. The only measurement given to the NYYC was Thistle’s waterline length at 85 ft, so there was great outrage and embarrassment when it turned out to be 1.46 ft longer when formally measured in New York just before the series. This mistake gave the NYYC carte blanche to do what they liked and Thistle was trounced 3:0.

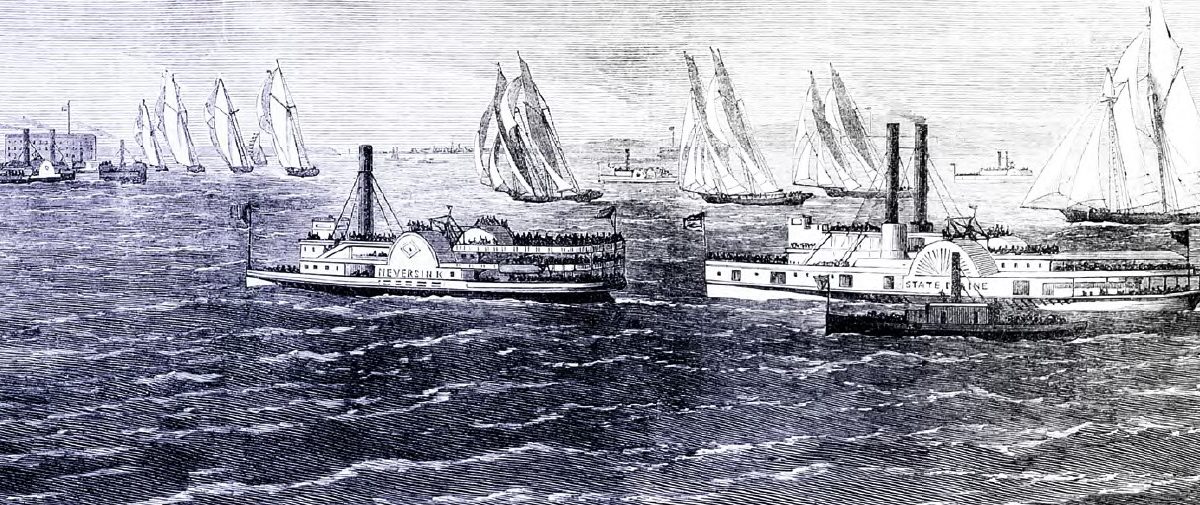

The experience led the Americans to strengthen the already one-sided Deed of Gift rules still further by demanding future challengers to furnish all measurement details of their yacht ten months before the match. That gave the NYYC members just enough time to build a yacht to outperform the challenger. Lord Dunraven was the first to face these one-sided rules. His 117 ft Valkyrie II was pitched against the 124 ft Nat Herreshoff designed centreboard cutter Vigilant and lost 3:0. Dunraven’s second challenge in 1895 became so mired in controversy that it took another four years for the dust to settle. He became convinced that the Americans cheated by adding ballast to sink their yacht Defender deeper to increase her waterline length, and became so outraged by the antics of the spectator vessels baulking the passage and taking the wind from his Valkyrie III, that he refused to start the last race. It ended with another 3:0 drubbing.

Two other wealthy challengers, Sir Thomas Lipton and aeronautical pioneer Sir Tom Sopwith, restored American faith in Britain’s gentlemanly sportsmanship. Between them they challenged for the Cup seven times over a period of 31 years, courteously smiling through each defeat. Lipton’s gentlemanly behaviour in particular won hearts and minds, for while his various Shamrocks lost on the water, Lipton’s Tea became one of the most popular brands in America, so for him at least defeat on the water was turned into a commercial success. Sopwith came closest to winning the Cup in 1934. His J Class yacht Endeavour won the first two races, lost the third through a tactical error, and might well have won the 4th had the NYCC committee been prepared to hear her protests brought against their defender, Rainbow.

There were in fact two bones of contention in that race. The first involved Rainbow’s duty as overtaking boat to keep clear of Endeavour during the pre-start manoeuvres. The second was Rainbow’s failure to respond to Endeavour’s luff soon after rounding the first mark, which forced the British yacht to bear away to avoid a collision. Photographs suggested that Rainbow was at fault in both incidents, but the committee ruled that Endeavour had failed to fly her protest flag immediately after the incidents and refused to hear the evidence. That caused outrage on both sides of the Atlantic and the memorable newspaper headline: ≫Britannia rules the waves and America waives the rules!≪ It was ever thus. Sopwith’s challenge withered to a 5:2 defeat and it took a further 49 years before the NYYC’s tyrannical rule came to an end when Australia’s Alan Bond used subterfuge and public opinion to beat the New Yorkers at their own game.

//

Text: Barry Pickthall. This article appeared in GOOSE No. 31