My teenage years were spent reading about pioneering sailors like Joshua Slocum, Bernard Moitessier and Robin Knox-Johnston. It was their hair-raising stories of huge seas, dramatic sunsets, and being at one with the oceans that first inspired me to get immersed in the sport. Like many others, the dream of course was to emulate their great voyages. Five decades on from the »Sunday Times Golden Globe Race«, i’ve finally been rewarded with a god-given opportunity to sail On Moitessier’s legendary yacht Joshua.

Now owned and maintained as a living museum piece by the French National Maritime Museum in La Rochelle, this distinctive bright red ketch is a national treasure in France and Moitessier the father figure of French solo sailing. It has taken a year of planning to gain permission from the French Government for her to be sailed over to England in 2018 to join the celebrations marking the 50th anniversary of the 1968/9 ≫Sunday Times Golden Globe Race≪. Joshua and her enthusiastic crew have been given a month-long licence to return to Plymouth and Falmouth, UK, in June next year for the start of the 2018 Golden Globe Race. Moitessier is best remembered as the man who, after rounding Cape Horn, turned his back on glory to continue to make a second circuit of the Southern Ocean – ≫because,≪ he said, ≫I am happy at sea, and perhaps to save my soul.≪ Instead of chasing after Knox-Johnston’s Suhaili for the Golden Globe trophy and £5,000 cash prize for the fastest circumnavigation, Moitessier turned east. The first the world knew of this dramatic change of heart was when he appeared off Cape Town about the time he was expected in the English Channel, and catapulted a film canister containing the famous message onto the bridge of an anchored tanker for the crew to pass on to Paris and London.

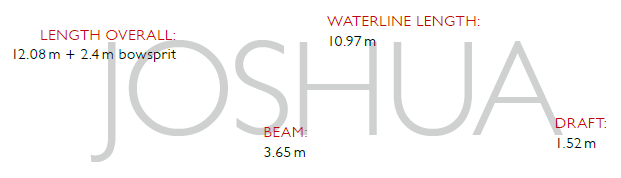

Biographer Peter Nichols believes the Frenchman became a hero, not so much for his epic voyages but for his epic ambivalence and human frailty. He was almost certainly bipolar; unstoppably enthusiastic and grimly depressive by turns, this wire, alternately taut and loose, threaded itself through everything he did and compounded the contradictions of his life and outlook. Much of this is reflected in Joshua. First launched in 1961, French naval architect Jean Knocker took 14 months to turn Moitessier’s detailed sketches into a workable plan. 40 ft overall with a 6 ft bowsprit, Bernard chose steel as the best construction material to minimise maintenance and maximise on strength. He wanted a yacht with a good performance upwind. His previous boats had all been traditional Asian built fishing boats and junks that lacked any sort of performance closehauled. He wanted shallow draft to explore the coral seas. Knocker had suggested a centreboard but Bernard refused. In the end, they compromised on a 1.5 m draft. Moitessier also specified a Norwegian styled pointed stern which he said divides and eases a breaking sea’s violent push when running. He also wanted a Marconi ketch rig. He liked the idea of a comfortable interior divided between two independent cabins with full headroom in each, though the Norwegian stern shape made the aft cabin less roomy. He used this for storage, which gave him all the more space in the main cabin to eat, navigate and sleep. When the weather was bad, he could also steer the boat from inside the main cabin, by simply removing the tiny spoked wheel on the outside of the cabin bulkhead, and re-attach it on the opposite end of the spindle inside.

Joshua was launched as a bare hull early in 1962 and finished in something of a rush

Moitessier’s first booking for the sailing school he had started was on April 15! Her main mast was a 57 ft heavy telegraph pole rigged with galvanised wire scrounged from the same telephone company. Her mizzen mast had similar parentage. Halyards, sheets and mooring ropes were pulled from garbage bins, then spliced into usable lengths. There were no winches. Instead, he relied on a block and tackle named Attila to tension the lines. There was no money for an engine either, and Moitessier planned to ship two sets of oars before a friend took pity and donated a 2-stroke 7-hp engine. Joshua was readied just in time, but by the end of the season he and his new bride Francoise were exhausted by it all. That was when the idea of a honeymoon cruising around the world came up. The two set off from Marseille bound for Tahiti via Panama in 1963. Three years later, they returned non-stop via Cape Horn finishing up in Alicante, Spain, to record the longest passage ever made in a sailboat. The voyage was far from easy. Moitessier described one storm as an ≫end of the world gale≪. For six days, they endured hurricane strength winds, which threw up enormous waves – ≫breakers 150–200 metres long, breaking without interruption ≪. Moitessier employed all his trailing lines and sea anchor to slow their progress but Joshua still came within an ace of capsizing. How had the Argentine sailor Vito Dumas coped during his solo circumnavigation via the three great Capes aboard his 31 ft double-ended ketch Legh II back in 1942/3? While Bernard wrestled with the wheel inside Joshua’s cabin, Francoise read the passage where Dumas revealed his secret: ≫To escape the fury of the sea, keep up your speed.≪

There was no way he could reel in the warps or sea anchor, so Moitessier cut them free

Joshua became liberated, responding to any touch to the helm to take the breaking waves on her quarter. It was the following year that Francis Chichester became the first to complete a one-stop solo circumnavigation aboard Gipsy Moth IV. That got everyone, including Moitessier, thinking about attempting to become the first to do it non-stop. ≫The Sunday Times≪ newspaper stepped in to make a race of it. The Frenchman was appalled. When approached by the paper, Moitessier exploded. ≫This proposal makes me want to throw up. It is a sacrilege to turn what is the ultimate challenge into a race.≪ Undaunted, the man from ≫The Sunday Times≪ persisted with a suggestion that the paper amends its rules to allow a competitor to start from France. To their utter amazement, Moitessier performed a complete volt face. ≫I shall leave Toulon as soon as possible for Plymouth where I shall start the race.≪

There was a barb: ≫If I’m both the first home and the fastest, I’ll snatch the cheque without saying thank you, auction off the Golden Globe and leave without a word for ›The Sunday Times‹. That way I will make a public statement of the contempt I feel for your paper’s project!≪ Moitessier was joined in Plymouth by his friend Loick Fougeron who entered his 30 ft steel cutter Captain Browne where they made friends with two other competitors, Lieutenant Nigel Tetley with his 40 ft trimaran Victress and Commander Bill King who had been the first to put his name down for the Sunday Times challenge with his monohull Galway Blazer II. Robin Knox-Johnston set sail from Falmouth on June 14. Moitessier and Fougeron began the chase from Plymouth on Thursday August 22nd. The forecast predicted better weather the following day, but there was no way that Bernard would start on a Friday. Unfettered by trailing warps and sea anchors, Joshua made good speed. By the time the French yacht reached Cape Horn 17 days behind Suhaili, the bigger red yacht had shrunk Knox- Johnston’s lead by 40 days. Could Moitessier have caught the Englishman on the final leg back up the Atlantic? Five decades on, Sir Robin admits it would have been close. Opinion in France of course is that their man would have won. In fact, there is a common myth in French parlance that Moitessier was first to round Cape Horn.

Moitessier and Joshua finally pitched up in Papeete, Tahiti, on June 21 1969 after 300 days at sea.

By all accounts, Filli rebuilt the yacht beautifully and sailed her to Seattle where American Johanna Slee, a professional mariner, bought her. In 1989, Virginia Connor spotted the distinctive red ketch in Seattle and sent a picture to Voiles et Voiliers magazine. Once authenticated, Patrick Schnepp, director of the French National Maritime Museum in La Rochelle flew across in mid-winter to purchase her and arranged for Joshua to be shipped back to France. There, a team of Moitessier disciples painstakingly restored the yacht back to near original condition. The metal masts fitted after the hurricane remain, a new engine has been fitted, and the aft cabin is now fitted out with bunks to give more people the opportunity to sail on her.

or the rest, it is exactly as Moitessier had her. Everything about Joshua is minimalistic and simple. Look at the deck cleats – radiused pieces of steel pipe welded to the deck with two horns drilled through at right angles. Galvanised chain is used for the top lifelines and lower parts of the standard rigging. Amidships, just astern of where Moitessier practiced his yoga each day, the simple dorade with a tyre inner tube looking like an elephant’s trunk continues to provide fresh air below, collapsing whenever there is green water on deck. The bowsprit is also original, made from steel pipe. When it buckled sideways during Moitessier’s solo circumnavigation, he simply rigged up his handy billy block and tackle to pull it back into shape and replaced the broken stay. It remained that way for the rest of the voyage. There was a gentle 10-knot breeze when we hoisted sails off Les Sables-d’Olonne and Moitessier’s yacht responded beautifully. Once away from land she proved very close-winded, pointing much higher than Suhaili can, and cut through the swell with little ado. With her cutter rig set, she presents a cloud of sail and has the ballast to carry it upwind through quite a large wind range. There is no roller furling so the hanked jibs have to be pulled down by hand with one person having to climb out onto the bowsprit to retrieve the sail. Suhaili by contrast has a highfield lever to slacken tension on the stay and allow the sail to be pulled into the bow. Returning to port, we ran back on a broad reach, making 5 knots without fuss or setting a mizzen staysail. Joshua was a delight to sail, and it is little wonder that there are several hundred replicas floating around the globe – she makes a great blue water cruising yacht.

//

Text: Barry Pickthall. Thhis article appeared in GOOSE No. 26